We start the new year off by revisiting an important skill for developing software: version control.

You can also download the original slides.

What you’ll need

- git: https://chryswoods.com/introducing_git/installing.html

- A terminal

- Windows: “Git Bash”

- A text editor like Notepad, nano, gedit

- Four other commands:

mkdir: “Make directory” for making new directoriescd: “Change directory” to change into a directoryls: “List” to list the contents of a directoryrm: “Remove” to remove (delete) a file

What is version control?

What is version control?

- Version control systems record changes to a file/set of files over

time

- Not just software! This talk is under version control

- Allows you revert files back to a previous state, compare changes over time, see who last modified something, etc.

- Instead of keeping multiple copies of the same file, normally just store the differences (“diffs”) between versions of the files

Why is version control important?

- Tracking versions

- Know instantly which is the latest version

- Roll back to previous versions

- See history of project/file/line

- Find out when bugs were introduced

- Maintain/compare different versions

- Coordination between developers

- Easier to keep track of when changes are made

- Easier to work on separate features

- Easier to merge distinct changes from separate developers

- Easier to resolve conflicts on same features

- Tracking who made what changes

If it’s not under version control, it doesn’t exist!

The gist of git

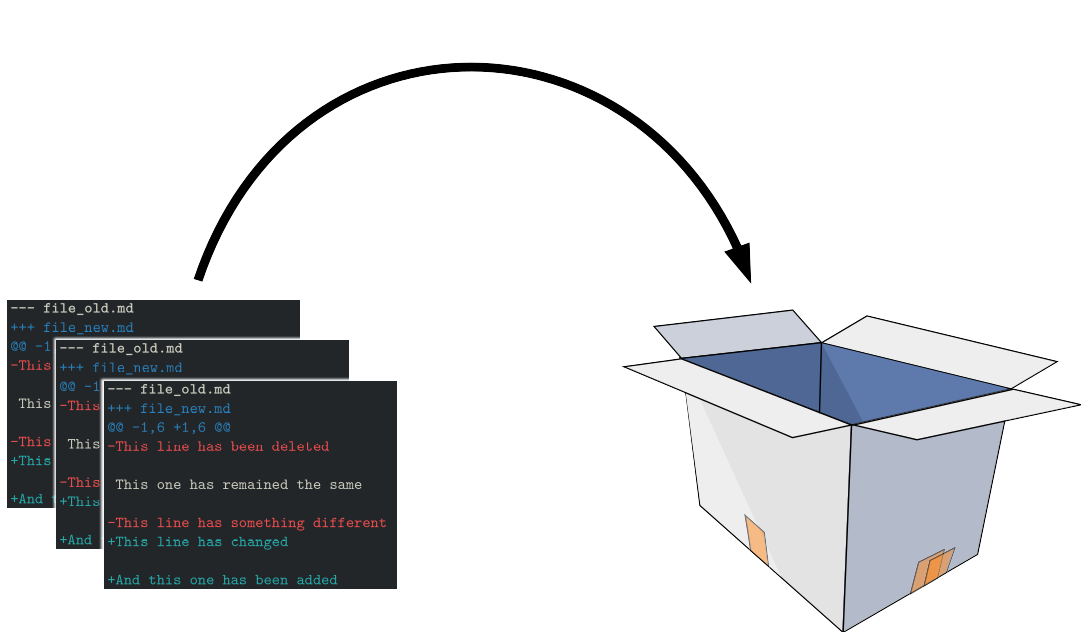

The building blocks: diffs

file_old.md

1 This line has been deleted

2

3 This one has remained the same

4

5 This line has something different

6

file_new.md

1

2 This one has remained the same

3

4 This line has changed

5

6 And this one has been added

diff file_old.md file_new.md

--- file_old.md

+++ file_new.md

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

-This line has been deleted

This one has remained the same

-This line has something different

+This line has changed

+And this one has been added

- Shows differences between individual lines

- Lines beginning with “

-” have been removed - Lines beginning with “

+” have been added - Changed lines are shown as removal plus addition

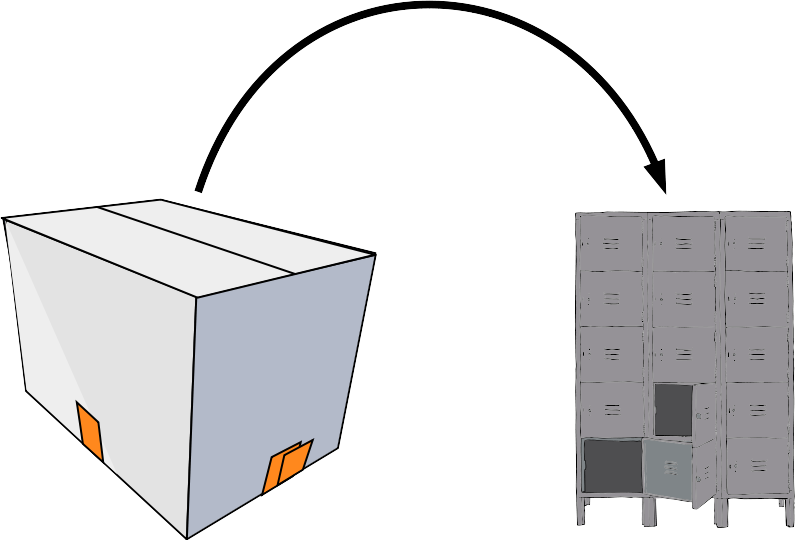

Add diffs to a staging area

Commit the staging area to the repository

Commit the staging area to the repository

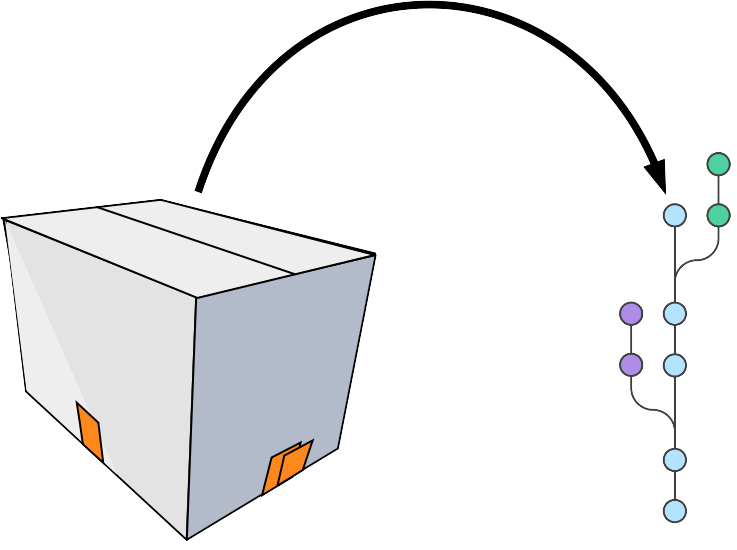

Sync with other people’s repositories

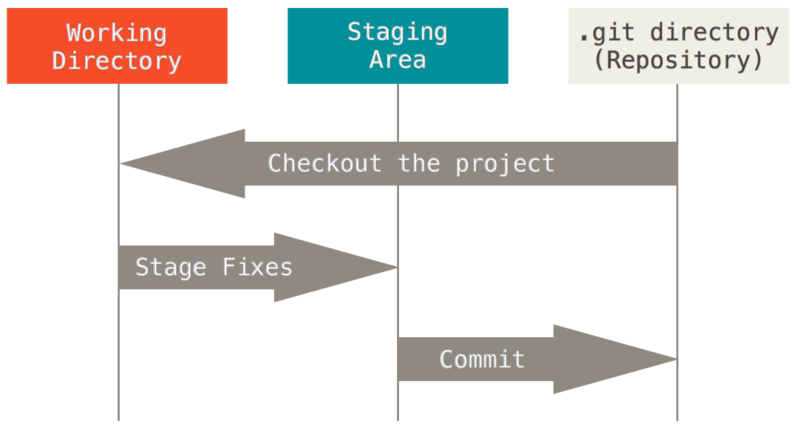

The Three Stages

- Important to understand correctly

- Three main states that files can be in:

- Committed: data stored in repo

- Modified: file is changed but not committed

- Staged: modified file marked to go into next commit

{width=90%}

{width=90%}

Using git

Graphical interfaces

For Mac and Windows:

- Github Desktop: https://desktop.github.com/

For Linux:

- git-cola: http://git-cola.github.io/

For Emacs:

- magit: https://magit.vc/

Zeroth step

Very first time using git on a system

- Need to tell git who you are:

$ git config --global user.email "you@example.com"

$ git config --global user.name "Your Name"

- Might also need to set text editor:

$ EDITOR=nano # terminal-based

$ EDITOR=gedit # GUI, Ubuntu only

$ EDITOR=notepad # GUI, Windows only

First steps

Making a repository

- Create a new empty directory and change into it

-

Initialise a new git repo

$ mkdir learning_git $ cd learning_git $ git init - Let’s see what it looks like

-

What do you see after typing each of the following commands?

$ ls $ ls -A $ git status

Getting help

$ git <command> --help

git status

git status: Show the working tree status- Glossary “Working tree”: what the repository directory looks like, including any changes

- Going to be our most used command today!

- Use it whenever you’re not sure what’s going on

Initial commit

- Create a new file called “README.md”

- Add some text to the file

- What does

git statusshow now? - Follow the instructions to add your new file to the staging area

-

Check

git statusagain$ git status $ git add README.md $ git status

$ nano README.md

# Hello World

Today we're learning about git.

We will use git to track changes

to this file over time.

This is a deliberate tpyo that

we'll fix later.

Initial commit

-

Now we need to actually commit our commit

$ git commit - This will pop up your

EDITOR - The traditional first commit message is “Initial commit”

- Now check

git statusagain

ASIDE: vim

- With plain

git commit, your default editor should pop up- If you hate it, change your

EDITORvariable

- If you hate it, change your

- If you haven’t changed it, it’s probably

vim - Two modes: “insert” and “command”

ito be able to type textESCto enter commandsESC :qto quitESC :wqto write and quit

Previously…

$ git add README.md

$ git commit

git add

git add <file>: Add file to the index- Glossary “Index”: the stored form of the working tree, i.e. the staging area, our “box”

git commit

git commit: Record changes to the repository- Until you run

git commit, the changes made to the staging area (index) remain separate from the working tree and repository

Writing commit messages

- Writing good commit messages is a skill!

- Commit messages serve as documentation for your project

- Finish the sentence: “This commit will…”

Good

- Fix bug in boundary conditions

- Add new routine for calculating potential

Bad

- update code

- I fixed some stuff

First steps

Making our first change

- Fix the typo in

README.md - Time for

git status -

Ok, but how to actually see the changes?

$ git diff # All files $ git diff <file>... # Just certain files - Press

qto quit the “pager”

Commit the change

-

It’s a two-step step:

addthencommit$ git add <file> $ git commit -m "Fix typo in README"

git diff

git diff: Show changes between commits, commit and working tree, etc- Without arguments, or with just files, shows differences between the working tree and the staging area

- Use

git diff --stagedto see the difference between staging area and latest commit (i.e. what’s going into the next commit)

Updating the staging area

- Make a change and

git addit - Now make another change to the same bit of that file

- Check

git status, what do you see? - Try

git diff, thengit diff --staged, what’s the difference? git addyour second change, and try the twodiffcommands again

Updating the staging area

# Edit file

$ git add <file>

# Edit file again

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

$ git add <file>

$ git status

$ git diff

$ git diff --staged

Looking back

- Make some more changes and make two or three more commits

-

View the history so far:

$ git log -

View a particular commit in more detail:

$ git show <hash> - Glossary “commit hash”: a 40-digit hexadecimal “hash” that uniquely identifies a commit. Generally only ~7 digits are needed. The largest projects need upto 12

git log

git log: Show commit logs- There are lots of options here!

- Lots of ways to format the log, or search for particular commits

- Some useful ones:

--oneline: One line per commit--all: Show all branches--graph: Show a graph of branches

git show

git show: Show various types of objects- Also lots of options for formatting the output, etc.

Undoing unwanted changes

- Delete your file!

rm README.md

- Check

git status– can you see how to get it back (i.e. discard the change)?

Undoing changes to the index

- Make a change to a file and now add but don’t commit

- The usual –

git status– how do you remove something from the staging area?

Undoing things

# Make a change to a file

$ git restore <file>

# Or on older versions of git:

$ git checkout -- <file>

# Make another change

$ git add <file>

$ git restore --staged <file>

# Or on older versions of git:

$ git reset HEAD <file>

git restore

git restore <file>: Restore a file, discarding local changesgit restore --staged <file>: Remove a file from the staging area (index)- This command was added in January 2020, so your OS might only have an older version!

git checkout

git checkout [options]: Switch branches or restore working tree files- Glossary “checkout”: modify the working tree en masse

-

Remove unwanted changes to a file:

$ git checkout -- <file> - Note: one of the few things in git that can’t be undone!

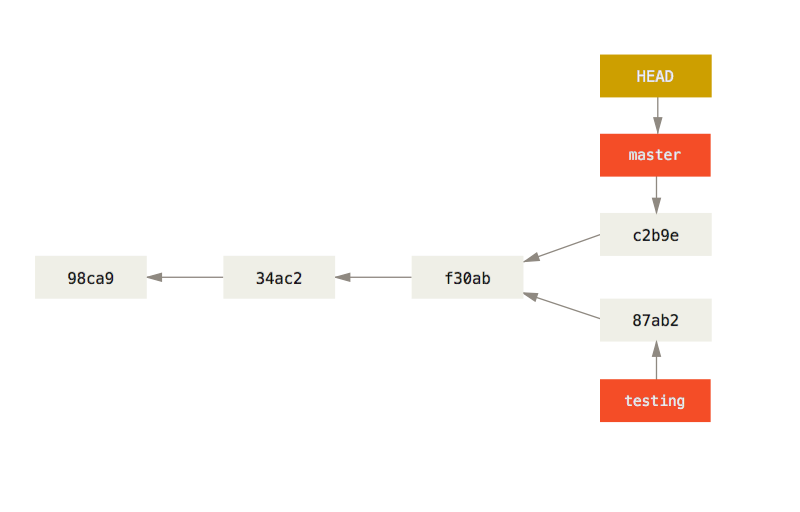

git reset

git reset: Reset current HEAD to the specified state- Glossary “HEAD”: the current commit that the working tree is based on

resetcan change the working tree and/or staging area, but doesn’t change HEAD, i.e. what commit you’re working from-

Remove a file from the staging area (but leave the changes in the working tree):

$ git reset HEAD <file>

Beyond the basics: branches

What is a branch?

- A git repo is like a tree (technically a directed acyclic graph), and like trees has branches

- More practically, a branch is just a label for a particular commit

- Can have lots of different labels on a given commit, i.e. lots of branches all the same

- Default first branch is called “master”

- You’re not forced to share your local branches with others

- Can experiment and explore, then chuck away branches that didn’t work out

- Making a new branch is always safe!

Making a new branch

git branchcommand is normally not what we want- Make a new branch and check the

statusandlog:$ git switch --create new_branch # Or on older versions of git: $ git checkout -b new_branch $ git status $ git log

Switching branches

-

Switch back to master, check

statusandlog:$ git switch master # Or older versions: $ git checkout master $ git status $ git log

git switch

git switch <branch>: Switch to<branch>git switch --create <branch>: Create new branch<branch>and switch to it- This command was added in January 2020, so your OS might only have an older version!

Making changes on a branch

- Switch back to your new branch

- Create a new file, add some text and save it in your repo

- Add and commit this new file

- Let’s look at a summary of all our branches:

$ git log --oneline --all --graph - Can you see where

master,HEADand your new branch are? - Switch back to

master– what’s happened to your new file?

Making changes on a branch

$ git switch <your branch>

# Add a new file

$ git add <new file>

$ git commit -m "Change text on a branch"

$ git log --oneline --all --graph

$ git switch master

$ ls

Moving forward: Merging

Merging

- Branches are only really useful if we can get those changes back into our main branch

- Merges are probably the biggest cause of problems, as it can be a tricky problem!

- Remember: it’s always safe to make a new branch and try something out there!

- Several different ways to do a merge, with differing results

Fast-forwarding

- This works when the branch being merged from was forked from the tip of the branch being merged into

- Often the nicest way to merge if it’s possible

^ C <-- branch2 | | | B | / time A <-- branch1

Fast-forwarding

- This works when the branch being merged from was forked from the tip of the branch being merged into

- Often the nicest way to merge if it’s possible

^ C <-- branch2 > C <-- branch1, branch2 | | > | | B > B | / > | time A <-- branch1 > A

A simple case

- You should have two branches:

masterand<your branch> - Only difference should be

<your branch>has an extra file in it - Very simple to merge this case!

- Checkout master and

mergeyour branch -

What does the full log look like now?

$ git switch master $ git merge <your branch> $ git log --oneline --all --graph

git merge

git merge: Join two or more development histories together-

From the branch you want to merge something into, run

$ git merge <other branch> -

If you run into trouble, abort the merge, create a new branch from your “main” branch and try things out in there

$ git merge --abort $ git switch --create test-merge-branch

Non fast-forwarding

- If there are any “conflicts” between the two branches, it’s a little trickier

- You’ll need to resolve the conflicts, and a special “merge commit”

will be created

- This is special as it has two parents

-

Some people/projects prefer to always have a merge commit as this may be easier to remove a feature if it has multiple commits

^ C <- branch1 | | B <- branch2 | |/ time A

Non fast-forwarding

- If there are any “conflicts” between the two branches, it’s a little trickier

- You’ll need to resolve the conflicts, and a special “merge commit”

will be created

- This is special as it has two parents

-

Some people/projects prefer to always have a merge commit as this may be easier to remove a feature if it has multiple commits

> D <- branch1 (merge commit) > |\ ^ C > C | | | B > | B <- branch2 | |/ > |/ time A > A

Fixing conflicts

- Conflicts happen when both branches touch the same line(s) in a file

- Conflicts are marked with a diff-like syntax

- To resolve the conflict, just go to the conflicting files and edit them appropriately

-

There are lots of tools that can help you with this, e.g. ediff, meld, diff3

<<<<<<< HEAD line changed in branch1 ======= line changed in branch2 >>>>>>> merging branch - Just delete all the special markers and the lines(s) you don’t want to keep

- Sometimes you want some combination of both regions – just edit the lines to keep what you want

- You can bail out of a merge with

git merge --abort

Creating conflicts

- Make a new file call

conflicts.txtwith the contents “some words” - Commit this file to

master - Now create and checkout a new branch called

conflict-branch - Change

conflicts.txtto read “some more words” - Commit this file on

conflict-branch - Checkout

masteragain and changeconflicts.txtto read “some other words” - Commit this file on

master - Now try to merge

conflict-branchintomaster - Fix the conflict, save the file

$ # Add "some words" to conflicts.txt

$ git add conflicts.txt; git commit

$ git checkout -b conflict-branch

$ # Change conflicts.txt to "some more words"

$ git add conflicts.txt; git commit

$ git checkout master

$ git log --all --oneline --graph

$ # Change conflicts.txt to "some other words"

$ git add conflicts.txt; git commit

$ git merge conflict-branch

# Remove conflict markers from conflicts.txt

$ git add conflicts.txt; git commit

$ git log --all --oneline --graph

Rebasing

- DANGER! This rewrites history!

- This has the biggest potential to cause headaches

- Rebasing a branch onto another one means to change the first branch’s “base” to the new branch

- It works by “replaying” the commits on top of the second branch

^ C <- branch1 | | B <- branch2 | |/ time A - DANGER! This rewrites history!

- This has the biggest potential to cause headaches

- Rebasing a branch onto another one means to change the first branch’s “base” to the new branch

- It works by “replaying” the commits on top of the second branch

> B' <- branch2 ^ C > | | | B > C <- branch1 | |/ > | time A > A B'contains (roughly) the same diffs asB

Stashes

- Very often the case that you want to switch branches, but you have made changes that either clash with the other branch, or you just don’t want to carry over

- Stashes are like commits on “anonymous” branches

- They save both your staged and unstaged changes, then discard them from your working tree

- Change your file, then

stashit - View the stashes with

stash list, and re-apply the latest stash withstash apply

$ git stash

$ git stash list

$ git stash apply

What next?

Applying this to your projects

- Make any existing project into a git repo:

$ git init

$ git add *

$ git commit -m "Initial commit"

- Come along to our drop-in Code Clinic in two weeks to get help!

Working with others

- git does not enforce a particular way of working with other people

- Easiest method is “feature branches”

- Everybody works in branches off the main “master” branch

- When it’s ready to share with others, make a “pull request”

- Other people can check your work

- Easy to resolve conflicts

Further reading

- Chris Wood’s tutorial: https://chryswoods.com/introducing_git/

- Git book: https://git-scm.com/book

- Atlassian tutorial: https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials

- Codecademy: https://www.codecademy.com/learn/learn-git

- Software Carpentry https://swcarpentry.github.io/git-novice/