- Could you find a document you wrote in 2007?

- Could you explain how you got the figures or results in that document, and repeat it if needed?

Most of us are buried in data rather than managing it, but:

- Spending a little time thinking about how (and what) you store now can save a lot of time later

- You don’t have to make big changes at once: small things can make a big difference

You can download the slides for this talk here.

Reproducing old results

Example scenarios:

-

Finishing PhD thesis: You need to modify a graph for your thesis, adding a few data points and reformatting it to look nice. Unfortunately you made the graph you have in your first year. Can you find or reproduce your analysis?

-

A new collaborator contacts you, and would like to build on work you published 5 years ago. Can they get the inputs and code to use as a starting point?

Both of these have happened to me, and are not uncommon…

Funding rules

In addition to being useful for your future self, keeping records is now a funding requirement. https://www.epsrc.ac.uk/about/standards/researchdata/

Principles

- EPSRC-funded research data … should be made freely and openly available with as few restrictions as possible in a timely and responsible manner

- EPSRC recognises that there are … constraints on release of research data.

- Sharing research data is an important contributor to the impact of … research.

- EPSRC-funded researchers should be entitled to a limited period of privileged access to the data they collect to allow them to work on and publish their results.

- Institutional and project specific data management policies and plans … should exist for all data. Data with acknowledged long term value should be preserved and remain accessible and useable for future research.

- Published results should always include information on how to access the supporting data.

Funding rules

In addition to being useful for your future self, keeping records is now a funding requirement. https://www.epsrc.ac.uk/about/standards/researchdata/

Expectations

- Organisations will promote awareness of these principles and expectations…

- Papers should include a statement describing how supporting data may be accessed

- Metadata describing the research data is made freely accessible on the internet

- What research data exists, why, when and how it was generated, and how to access it.

- It is expected that the metadata will include a robust digital object identifier (DOI).

- Ensure that research data is securely preserved for a minimum of 10 years

What to do? The short version

- Run simulations with an identifiable version of the code

- Document and keep all inputs used to produce published results

- Document all post-processing steps from simulation output to graph

- Put this information somewhere safe, and record its existence

Note: Something is better than nothing!

1) Preserve your code

- Code should be version controlled (git, svn, hg,…)

- Make sure you run simulations with a checked-in version

- Record the version used with the data

- If possible make this automatic: The

makeprocess can record the version This can be stored in the code, then printed/saved to output - Otherwise put it in a README file

- If possible make this automatic: The

- Store the code somewhere safe (10 years safe)

Example (C/C++) : makefile

VERSION := $(shell git rev-parse HEAD) # Get git commit

SOURCEC = mycode.cxx

TARGET = mycode

OBJ = $(SOURCEC:%.cxx=%.o)

$(TARGET): $(OBJ) makefile

g++ -o $(TARGET) $(OBJ)

%.o: %.cxx makefile

g++ -Wall -c $< -o $@ -DVERSION="$(VERSION)" # Pass to preprocessor

Example (C/C++) : mycode.cxx

#include <iostream>

#define VER1_(x) #x

#define VER_(x) VER1_(x)

#define VER VER_(VERSION)

int main() {

std::cout << "Code version: " << VER << std::endl;

return 0;

}

When run, this produces:

Code version: cdf9b8d6df85d669afe26aeab6b538a3b0f64c54

1b) Preserve your code’s environment

Your code probably depends on other people’s code: libraries, compilers, operating systems, …

-

Record somewhere the versions of the libraries used. This could be with the code in a README: “This code is known to work with MagicLibary 1.2 and AwesomeThing 0.8”

-

Software containers bundle code and dependencies together

- Docker https://www.docker.com is probably the most widely used

2) Keep track of code runs

When exploring parameters, changing code, fixing bugs, it can be hard to keep track of runs, and most of them will probably not be useful

- It’s hard to know what might be useful later

- Having a system helps organise results, simplifies analysis, and is easier to remember

- Everyone has a system, but it’s good to think about what it is occasionally

2) Keep track of code runs

Simple parameter scans

When only a few parameters are changing, and the code is mostly fixed, nested directories can work:

ex/ ex-C-1.0/

area-1.0/ area-2.0/

nloss-0.0/ nloss-0.0/

nloss-1e3/ 0.25/

0.3/ 0.3/

0.4/ norad/

area-2.0/ area-1.0/

Note Remember to document what the parameters are!

2) Keep track of code runs

Exploratory testing

When code is changing and inputs are changing, nested directories or long directory names become unmanageable.

run-01 run-02 run-03 run-04 run-05

README

In the README file explain what each run is:

run-01 : Starting with standard test case foo

run-02 : Changing parameter bar from 1 to 2

-> Field values seem unphysical near boundary

run-03 : Fixed bug in someBoundaryFunction, retrying run-02

...

3) Document post-processing steps

Important: Automate as much of the post-processing as you can

- Repeating the analysis is a matter of re-running the script

- Makes changing, extending or fixing the analysis much easier

data = [ ("no carbon", "ex/area-2.0/nloss-0.0", 'o')

,("1% carbon", "ex-C-1.0/area-2.0/nloss-0.0", 'x')]

for label, path, symbol in data:

# Read data from path

# Analyse it

plt.plot(result, symbol, label=label)

plt.legend()

plt.savefig("figure1-carbon-comparison.pdf")

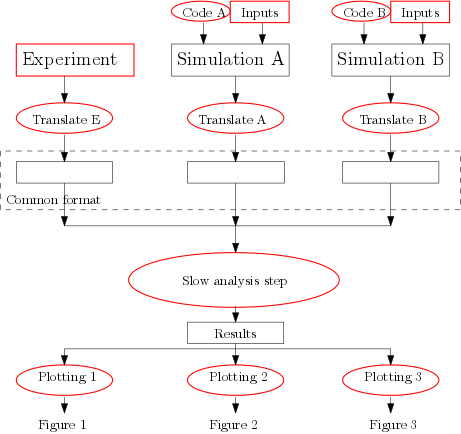

3) Break up complicated processing steps

It often makes sense to break up analysis into steps

- Translate different data sources to a common format, then apply the same analysis code to all of them

- Separate slow analysis from plotting

- Keep the scripts and essential inputs (marked red)

- Keep as much of the rest as you can, starting from the end and working back

4) Safely store code inputs and data

- The University shared filestore https://www.york.ac.uk/it-services/filestore/

- Long term, backed up storage

- Around 1Tb available to groups without charges

- The Archer Research Data Facility

- Long term backed up storage

- Not publicly accessible

- Code repositories

- Github https://github.com/ : Private repositories with Team plan, free academic use

- Bitbucket https://bitbucket.org : Unlimited private repositories for academic use

- CCPforge https://ccpforge.cse.rl.ac.uk/gf/

- Zenodo https://zenodo.org/

- Free hosting of data or software, up to 50Gb per submission

- Automatically assigned a DOI to include in publications

- Can be open, closed, or embargoed

- No transfer of ownership, flexible license

4b) Tell people about it

- The University’s PURE system can link papers to datasets (DOIs)

- Include a statement in your papers:

e.g. (Dudson, Leddy 2017)

All source code and input files used in this paper are available at https://github.com/boutproject/hermes (commit 91a783fa), along with BOUT++ version 3.1 available from https://github.com/boutproject/BOUT-dev configured with PETSc 3.5.4

e.g. (Nedelkoski et al 2017)

All data created during this research are available by request from the University of York Data Catalogue https://dx.doi.org/10.15124/249cbf0c-8e88-426b-b3ba-53d490e027ed.

Conclusions

- Good data management saves you time and headaches in the long run

-

Build on previous work rather than repeating it

-

Some tools available which can help: Jupyter notebooks, ELOG, Docker, …

-

Think about how you manage your data, and ways to automate and record it

-

For full EPSRC bonus points, there is DMPonline https://dmponline.dcc.ac.uk/

- York Research Data Management https://www.york.ac.uk/library/info-for/researchers/data/