Version control is one of the essential tools for anyone developing software of any kind, and will save you from a lot of sweat, blood, and tears when your hard drive fails or you spill tea all over your laptop. This presentation will give you an overview of why you need to use it, and how to get started using my favourite version control software, git.

This is a slight modification of the presentation I gave for the first Coding Club meeting.

Outline

- What is version control/git?

- Why is version control important?

- Basic git usage

- Working with others

What is version control?

Version Control System (VCS)

- Version control systems record changes to a file/set of files over time

- Not just software! This talk is under git

- Allows you revert files back to a previous state, compare changes over time, see who last modified something, etc.

Local VCS

- Naive versioning: separate folders for each version

- Slightly better: local database of changes

What is version control?

Centralised vs Distributed VCS

- Centralised VCSs: CVS, Subversion

- Have a single server than contains all the versioned files

- Can see what other people are working on

- Easier to administer a centralised VCS than local databases on each client

- If server goes down, can lose access to project history, etc.

- If central database is lost, everything not backed-up is lost

- Distributed VCSs: git, mercurial

- Clients don’t just checkout latest snapshot of files, repository is fully mirrored

- If server goes down, any client repo can be copied back to server to restore it

- Multiple remote repos work pretty well

Why is version control important?

- Tracking versions

- Roll back to previous versions

- See history of project/file/line

- Find out when bugs were introduced

- Maintain/compare different versions

- Coordination between developers

- Easier to work on separate features

- Easier to merge distinct changes from separate developers

- Easier to resolve conflicts on same features

- Tracking who made what changes

If it’s not under version control, it doesn’t exist!

How does git work?

git is local

- Vast majority of operations are local

- Doesn’t need to talk to remote servers to get e.g. history

- This means you can continue to work offline, including committing changes to the database

- Checking out a copy of the repository means you have a full copy

- You can copy your local version onto a USB stick and hand it to someone

- They now have access to the project history, can make changes, etc.

How does git work?

git has integrity

- Everything in git is check-summed

- References are to checksums

- git can immediately detect if data gets lost in transit or files are corrupted

- Checksums are done using SHA-1:

24b9da6552252987aa493b52f8696cd6d3b00373 - git stores everything, not by name, but by hash value of its contents

How does git work?

Snapshots

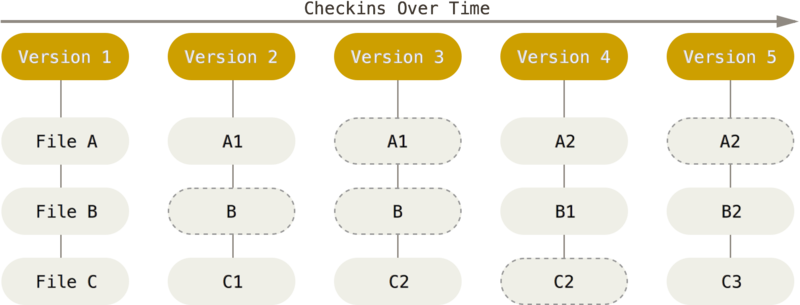

- git thinks of its data like a set of snapshots of a miniature filesystem.

- Every time you commit, it takes a picture of what all your files look like and stores a reference to that snapshot

How does git work?

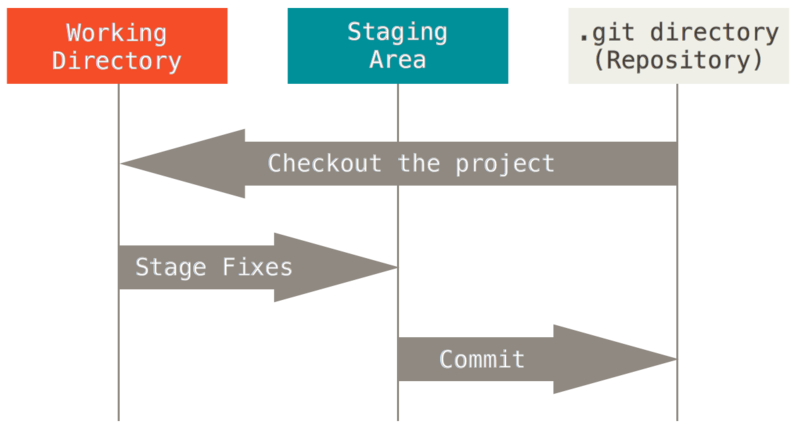

The Three States

- Important to understand correctly

- Three main states that files can be in:

- Committed: data stored in repo

- Modified: file is changed but not committed

- Staged: modified file marked to go into next commit

Branching

- Branching is the “killer feature” of git

- Very lightweight, easy to make new branch and throw away if not needed

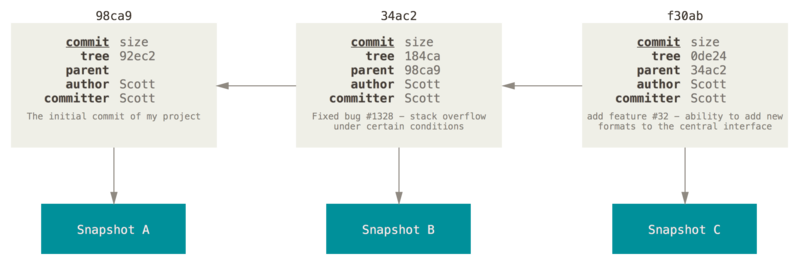

- Need to know how commits are stored

How does git store commits?

Branching

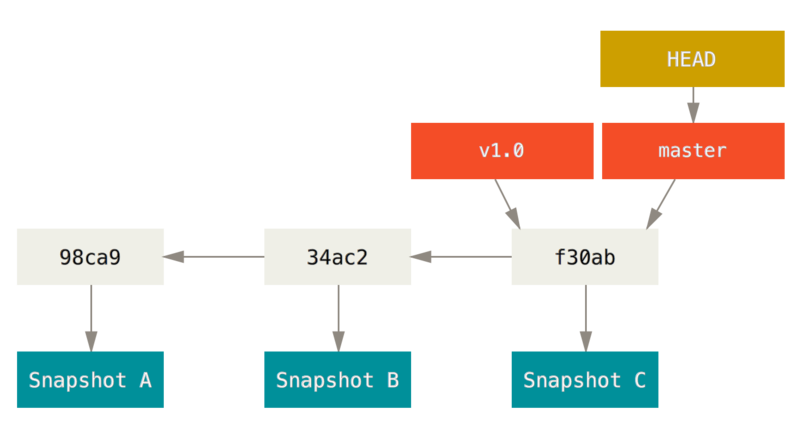

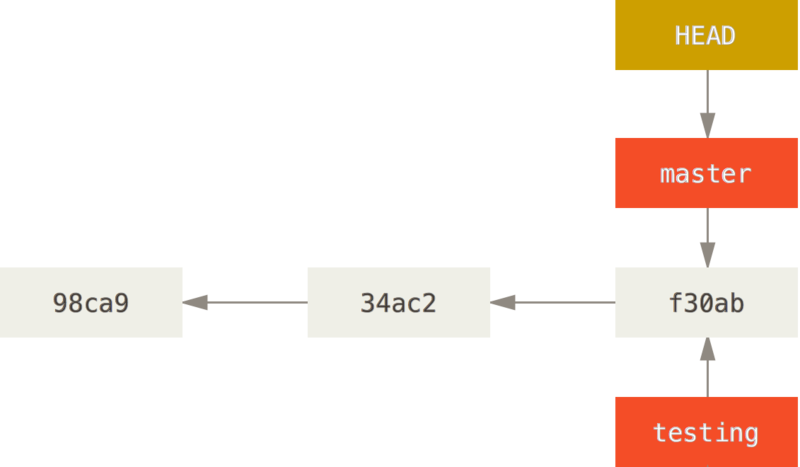

A branch is just a pointer to a particular commit

- HEAD is a special pointer to the current branch

Branching

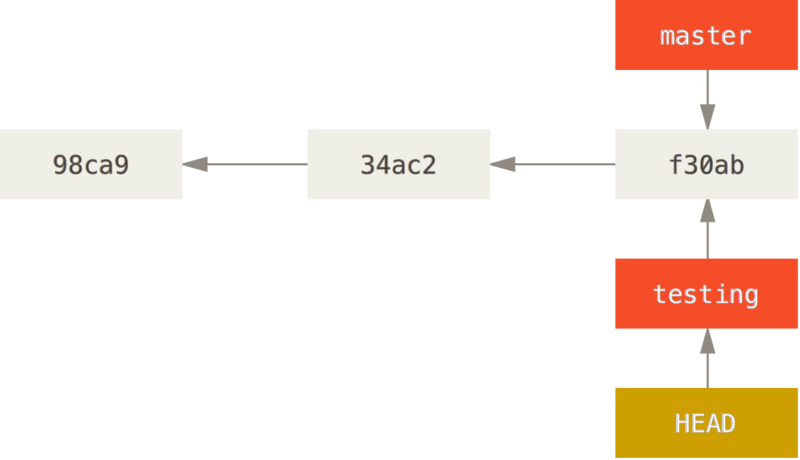

A new branch is just a new pointer

- Changing the branch just means changing what HEAD points to

Branching

A new branch is just a new pointer

- Changing the branch just means changing what HEAD points to

Branching

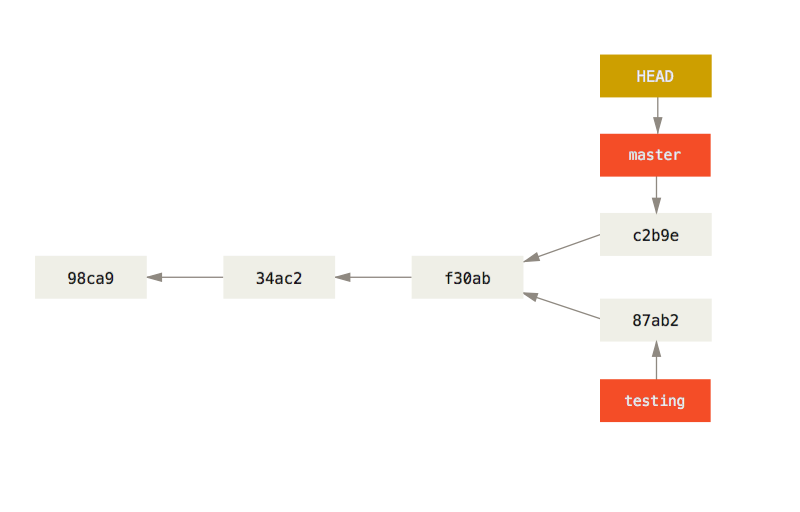

Branches can diverge

- New commits can be made to separate branches independently

Basic commands

Get started

# Initialise a bare repo

$ git init

# Add a new file

$ emacs newfile

$ git add newfile

$ git commit -m "Initial commit"

# Make some changes

$ emacs newfile

$ git status

$ git diff newfile

$ git add newfile

$ git commit -m "Add extra text"

More basic commands

Next steps

# View history

$ git log

# Get someone else's repo

$ git clone https://github.com/Username/some_repo.git

$ git clone /path/to/some_repo ./new_name

# Get help

$ git help add

$ git add --help

# Make a new branch

$ git branch branchname

# Switch to branch

$ git checkout branchname

Working with others

Sharing repos

- Various third party websites to host repos:

- GitHub

- GitLab

- Bitbucket

- University have command line-only service

- Host own web interface

Working with others

Centralised workflow

- Central “one true” repo

- Single master branch

- Useful for individual developers or small teams

Workflows

Feature branch workflow

- Central “one true” repo

- New features developed in separate branches

- Create “pull request” to request changes be merged into master branch

Forking workflow

- Each developer has their own fork of the repo

- Otherwise same as Feature branch workflow

- Developers push to their own forks, then submit pull requests from there

Working with others

Gitflow workflow

- Central “one true” repo

- New features developed in separate branches

- Strict model for how branches are laid out

- master branch

- feature branches

- development branch

- “next version” branch

- Only the “next version” branch can be merged into master

- Features get merged into development branch

- “Next version” gets branched off development branch and features are frozen

Resources

- Git book: https://git-scm.com/book

- Atlassian tutorial: https://www.atlassian.com/git/tutorials

- Codecademy: https://www.codecademy.com/learn/learn-git

Acknowledgments

Some material from Pro Git, Second Edition written by Scott Chacon and Ben Straub and published by Apress. Available here: https://git-scm.com/book

Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 3.0 Licence.